Season 1

·

Episode 2

·

38 Min

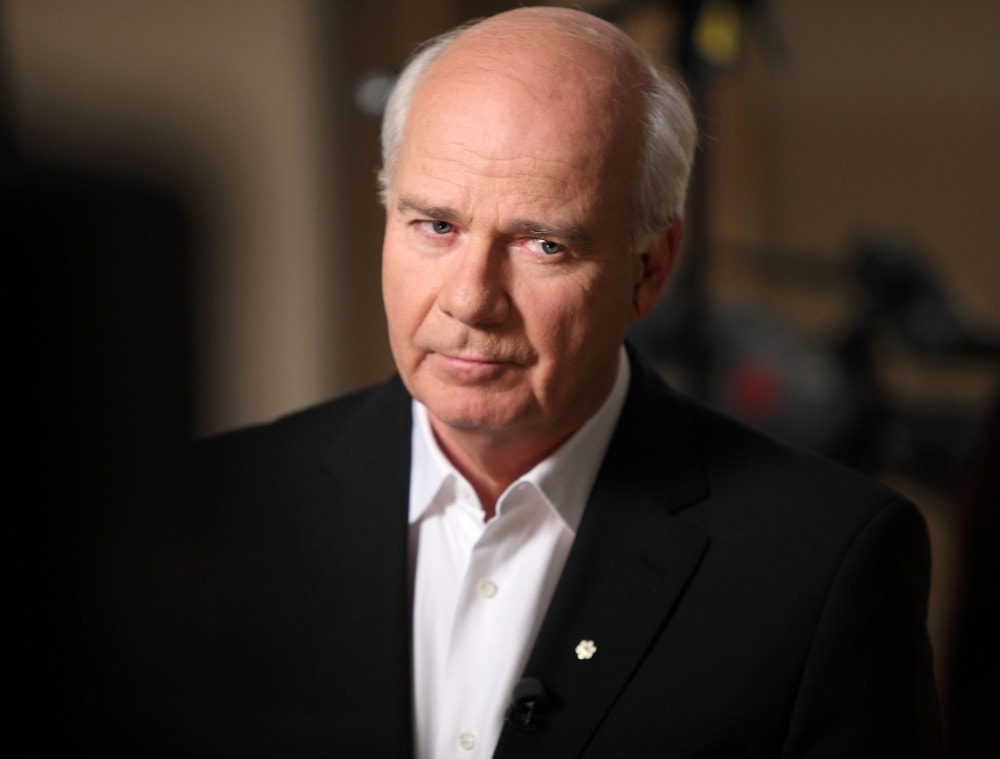

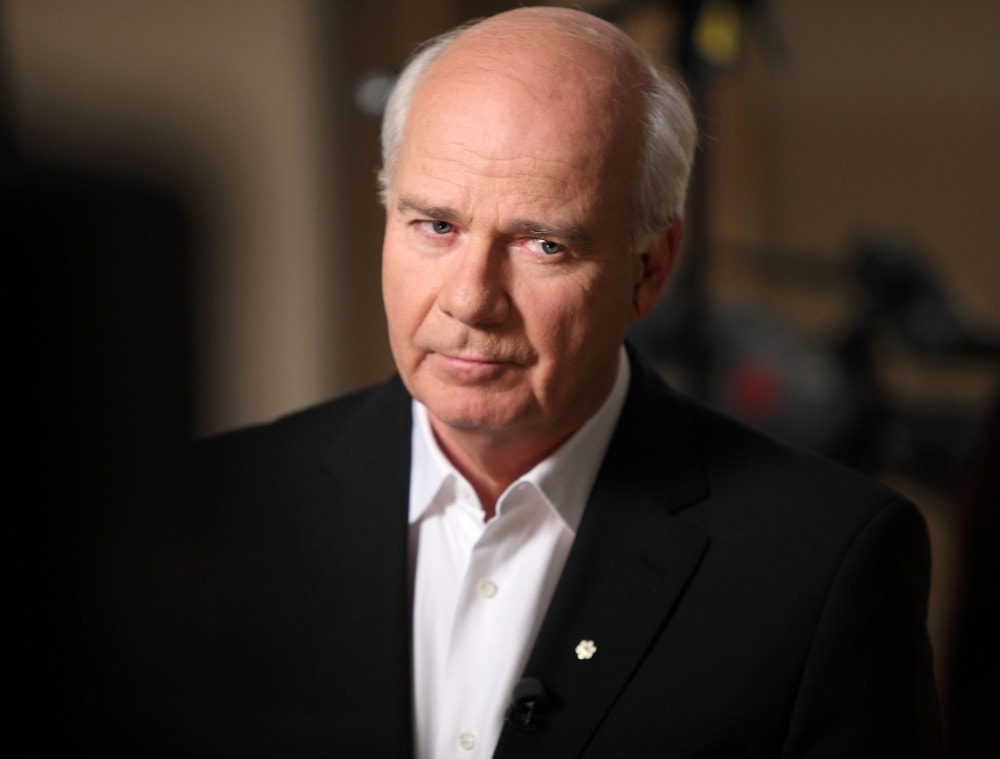

Peter Mansbridge

Peter Mansbridge is a long-time friend and fellow broadcaster. He is a British-born Canadian retired news anchor. From 1988 to 2017, Peter was chief correspondent for CBC News and anchor of The National, CBC Television’s flagship nightly newscast. He was also host of CBC News Network’s Mansbridge One on One. Peter has received many awards and accolades for his journalistic work, including an honorary doctorate from Mount Allison University, where he served as chancellor until the end of 2017. On September 5, 2016, the Canadian Broadcasting Corporation announced that Mansbridge would be stepping down as chief correspondent and anchor on July 1, 2017, after the coverage of Canada’s 150th-anniversary celebrations.

Full Interview

Episode Highlights

Peter Mansbridge - "Should The CBC Survive?"

Peter Mansbridge - "Should The CBC Survive?"

Peter Mansbridge - Early Newscast in Churchill

Peter Mansbridge - Early Newscast in Churchill

Episode Transcript

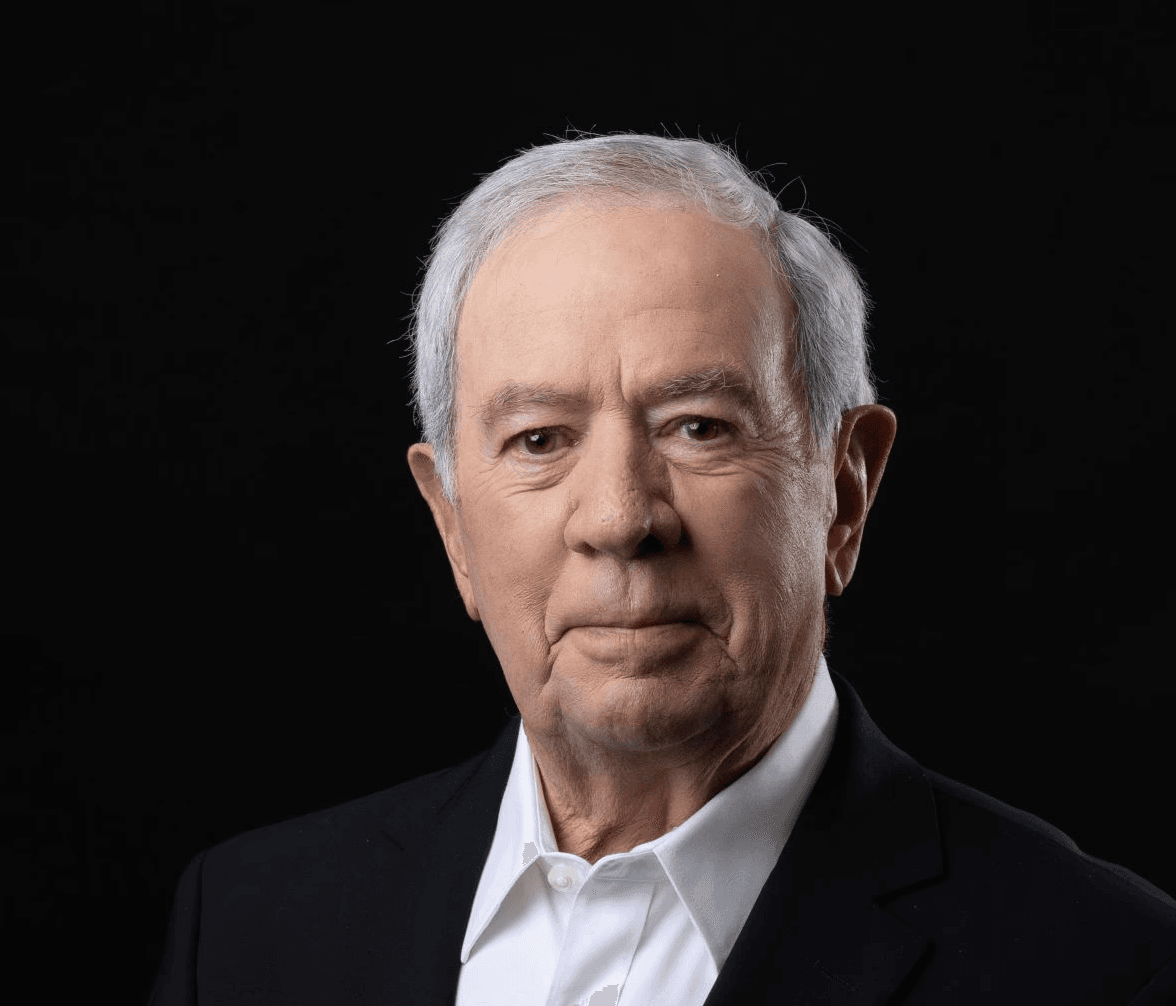

Tony Parsons

Hello, I'm Tony Parsons, and welcome to The Tony Parsons Show. As a news broadcaster and journalist for the past 50 years, I've reported on the major news events that have shaped our nation. I've interviewed prime ministers, premiers, thought leaders, and other people of distinction from around the world. My goal with this interview series is to help you, my audience, discover the person behind the credentials, while at the same time I'll invite them to share their professional insights, experiences, and aspirations.

I'm honored to welcome my colleague and fellow news broadcaster, Peter Mansbridge, to my show. As many of you are aware, Peter is best known for his five decades of work at the CBC, where he was chief correspondent of CBC News, and the anchor of The National for 30 years. He's won dozens of awards for outstanding journalism, has 13 honorary doctorates from universities in Canada and the United States, and received Canada's highest civilian honor, the Order of Canada in 2008. Now the host of the successful podcast, The Bridge.

Tony Parsons

Peter, I'd like to thank you for joining us today. It's great to have you with us.

Peter Mansbridge

It's great to be with you, Tony. I'm honored to be talking with you. I mean, it was very kind of you, all the nice things you say about me and my career. They could equally be said about you and yours. So it's an honor for me to be talking with you. Thank you very much. You know, I said "retired," but it seems to me that you're busier than you've ever been. I was thinking back to the first time you and I met, and that, if you recall, was at the University Golf Club. You were on the final green, I believe, and you were a judge, or were you running a contest for the putting?

Tony Parsons

Those were the old days of the Peter Russovsky Literacy Tournament. That's what it was. You and I supported Peter in his goals there, and they quickly learned that I wasn't much of a golfer, so they put me like on a putting grain, and I just pot against various people and collect a little more money out of them that way. But it was, that's a great golf course, a university golf course there, and it's a great area and met a lot of people there. I did that tournament, I guess, at least a half a dozen times. It was a great one, but always fun.

Peter Mansbridge

It was fun, it was a good time. I want to go back to the very beginning, and to the UK, where you were born, right?

Tony Parsons

Mm-hmm, I was. I was born in London in 1948.

Peter Mansbridge

We had kind of a similar background. Your dad was in the RAF. My dad was in the RAF. He was in bomber command, so he was based up at Lincoln with his Lancaster squad. And you know, had a distinguished career and war record as did your father. And that was the start, but I was only in England for a couple of years, because after the war, my parents, my dad was in the Foreign Service by then, and we went off to Kuala Lumpur in what was then Malaya to help it establish the independence and become Malaysia, as it did in the 1950s. And then we came to Canada, so I was when we came to Canada was about six, six years old, and we went to Otto. I was nine when we came here in 1948, and we went to a little town in Ontario called Feversham, about three, four hundred people after living in London for most of my young life and my poor mother. You can, you imagine, she cried for twelve days. It was just for her it was such a cult for shock. But my dad was, as you say, in the RAF, flight lieutenant, served in Iraq, and never got over the idea of wearing a uniform. He always loved to wear a uniform.

Tony Parsons

Let me take you back again, just a little bit. You were working in Winnipeg in an unusual job for now a broadcast journalist. You were discovered in Winnipeg?

Peter Mansbridge

Actually, I started working for an airline in Winnipeg, and they quickly moved me around. As this young kid, I was 19, 20 years old. Winnipeg was trained in Winnipeg. Then I worked in Brandon and Prince Albert. These were all for a couple of months at a time. Then they called me up and they said, "Hey, the guy in Churchill, the agent for our airline, which is called Transair, The guy in Churchill, Manitoba up on Hudson Bay is taking a holiday. So you got to go up there and fill in for him for two weeks. Nobody wanted to go to Churchill at that time, right? So up I went, and sure enough, a week after I'd been there, they called me up and said, "Hey, the guy quit. It's now your job. You're the new guy in Churchill." So that's what I was doing. And I was doing from loading freight to baggage, to selling tickets, to answering the phones, you name it, I did it all. Until one day they asked me to announce the flight over the PA system in the little terminal building. And it was a little, we're talking, this wasn't Vancouver International, this was Churchill, Manitoba, it was kind of one room. And so I got on there and I did, "Transair, Flight 106 for Thompson, The Pas, and Winnipeg now ready for boarding at gate one." There only was one gate, but it sounded really good. It sounded like the big boys did. And sure enough, there's somebody in the building, in the waiting room there, came up to me and said, "You've got a voice for radio. And I should know because I'm the manager of the CBC northern service station here in Churchill." And he said, "I can't get anybody to work the late night shift. And would you be interested?" And I said, "Well, I don't know anything about radio." And he said, "No, that wasn't the question. The question was, would you be interested?" So I said, "Sure." And so after a one-day course on how to run all the knobs on the control board, you know, those things from your days, you're in Stratford, Ontario, doing a country show or whatever it was you were doing on those days. Yeah, announce up, they used to call it. Yeah. So that's how I started. I started in Churchill, and it was the beginning of a 50-year career with the CBC.

Tony Parsons

Did you ever think you'd go on to replace Walt and Nash?

Peter Mansbridge

No, but you know, I thought about it. Even when I was in Churchill, because I, like you, I started with a music show. I was terrible at trying to understand music and stuff. And so I started a newscast. They didn't have one in Churchill, so I started one because I'd grown up in a family where we always kind of sat around the dinner table at night and talked about current events. And so I started a little, a little newscast. It was only like two or three minutes long when I'd started, and it eventually became half an hour of daily news in Churchill, which is quite something for a town of a thousand people. Um, but they had polar bears, which was always good for half the show every night. And so, you know, that's, that's how things started. And you kind of eventually make a name for yourself. And I was a reporter for 20 years before I started anchoring and then traveling all, all over the place in different locations.

Tony Parsons

How do you feel now about being retired?

Peter Mansbridge

It's interesting. I retired. I had told all my friends and I had told the CBC who wanted me to kept asking me to stay another year while they sorted things out, you know. I said, "I'm not, I am not going to do the national with a seven in front of my age. So take it from now that I'll be gone at 69." And I held true to that. And in 2015, I eventually gave them the clear signal, and by 2017, I was out. But I agreed to do some documentaries for the CBC for about a five-year period. And that was fun and a real experience for me. Having always been confronted with two-minute items and suddenly I was being given an hour to do a story, which was fantastic. But after that, I, you know, I wrote a, I've written four books since I retired. I do a, you know, a podcast like you, which is a lot of fun. I do it four days a week. It's on SiriusXM, the satellite radio service. And, you know, I give speeches. It sounds like I'm busier than I was, but like you, you do it in retirement, you do stuff at your own pace. I decide what I'm gonna do. Nobody's telling me what I have to do. I do things as I enjoy doing them and at my own pace. And I make sure I take the summers off, and I've just been doing that and it was great.

Tony Parsons

Looking back, what for you were some of the highlights of your career?

Peter Mansbridge

You know, I was so lucky because I got to work with so many great people, whether they were the people we see on the air, the correspondents, the reporters, or whether the people behind the scenes, the producers and the writers and the editors. And I think when people say, "Do you miss it?" I always say that's what I miss. I miss that camaraderie, that coming together to put a good product on the air and the feeling that you'd have at the end of the day and the discussions and the arguments that you'd have during the day about what needed to be on the program. So I miss that. I miss that a lot. And as I often tell young journalists who come to me and say, you know, "I'm not quite happy with where I am and what I'm doing." And I say, "Well, when you're in meetings for your program, what are those meetings like? Are they, you know, is there debate around what you're doing and covering?" And then they might say, "Oh, really?" I said, "Well, that's what you need. You need to be in a place in a newsroom where there is constant discussion and debate about the stories that you're covering." Now, you may have strong feelings they may end up not being accepted, but make the case. You know, try to convince others of what you're feeling or listen to the arguments of others, and maybe you'll be convinced by theirs, but you need that kind of discussion in a place. And I used to love those days. I mean, not every day was the exciting news day that we see in the movies. Some are kind of boring, and you're having a hard time trying to figure out what you're going to fill the program with.

Tony Parsons

True enough.

Peter Mansbridge

But a lot of days, you know, it was exciting, and it was, you know, it was worthy of the debate and the discussion. So I miss that. I miss, I miss the travel. I mean, I, you know, as first a reporter, and then as an anchor, when I accepted the anchor position and they asked me if I do that, I said, "Only if I can still travel occasionally, I want to get to the stories, especially whether it's, you know, where the national, it can't just be in downtown Toronto. You know, we got to be around." So, and one of my favorite places to go, and still is these days, was British Columbia. But I, you know, I did the national from every province, from all three territories, at least once, but usually half a dozen or a dozen times in some places. So that was important, but also traveling the world. And as the technology became easier and easier. As you said, Tony, you know, when we started, you had to, you know, sometimes to many half a dozen people with you to go on the road. They didn't have to be that way. It certainly doesn't have to be that way anymore for you to see about one-man band reporters where they do everything. They shoot it, they edit it, and they write it, and they do the whole bit. So it's a lot easier to take the show on the road as well. I took the show to Afghanistan a couple of times, to Iraq, to China, to all over Europe, the United States, South America, because it was not limiting by expense. It's only limiting by story. If you get to the story, you can tell the story, and you can tell it better when you're there than when you're in a studio in Toronto or Vancouver, wherever it happens to be. So I wanted to do that. Well, obviously, you couldn't do that all the time. But I did as much as I could in those days. I love, I love the thought of going to the airport, getting on a plane, and going off on some new adventure. So do I miss all that? Oh, yeah, absolutely. For sure, but you know, I was getting on, and it was time for younger blood, and I believe that then, and I believe it now, in whatever the job may be. I think there's definitely a need for experience and understanding based on what you've done in your career, but there's also a need for bringing new attitudes, new ideas into the system as well. So that's kind of where I land on that.

Tony Parsons

Things have changed now in the industry. What changes do you note that maybe social media has had a lot to do with?

Peter Mansbridge

Oh, yeah, it's pretty much everything to do with it. I mean, it started to change, and you remember this, it started to change in the 90s with the explosion of channels and competition and the 500 channel universe, and then the internet came and all these other options for news gathering started. And then when social media entered the picture, whether it was Facebook or Twitter or you name it, the challenge became deeper and more difficult because people were unsure of the nature of this new tool for social media, but they were more distrustful of its accuracy. And it's changed the face of the news business. Trust in news has slid. And there's no question about that, no matter who you watch, who you listen to, who you read. The client is questioning now because of disinformation and misinformation. What's accurate. And as you know, Tony, as well as anybody in the news business, truth is what matters. In fact, it's really all that matters is truth. And when you doubt that you're getting the truth, then you got a problem. And that's what all news organizations are trying to address now. And they thought it was going to be easy, it's not easy. And when you're at a point where people don't trust you, there's a serious question about the future for the news business. I mean, I'm sure we're gonna get through this, but it's tough right now. And people have a right to be concerned about the quality of the information they're getting.

Tony Parsons

Who would you have a rescue plan of any kind in your mind?

Peter Mansbridge

Well, I mean, it starts with making so many organizations more viable, more economically viable. You know, every day we read about another news organization or a broadcaster that's in trouble, is laying off people or shutting down. So that's one area of concern. Obviously, if you don't have the ability to be on the air or to print a newspaper, that's one part of the problem. But the other part is this trust thing. I really feel that we have to be more transparent. I keep talking about "we" Like it's like you and I are still in the business directly, but we're clients now so we're part of the picture, and we want to see a solution, and one solution on trust is to be more transparent about how we do our job. Like how do we decide what stories are worth telling? How do we decide what order they should be in? How do we decide how much time we should give to particular items? And then there's the more delicate stuff of, you know, when you start giving anonymity to certain sources to be able to break a story. How do you make that decision? Who gets anonymity? Who doesn't? How strongly do we look at their motives for wanting anonymity? Those are all issues that people worry about. When I talk to viewers or listeners or readers, those are the kind of questions they raise because they think we're biased or we're dealing in fake news and all that. So you have to be able to convince them that we're not, and to convince them we're not, you've got to show them how you do it, how you make the sausage. It's not always, you know, for them to, you can't do this every day, obviously, in a newscast, but every once in a while, you need to do it. You also need to admit when you're wrong. You know, you make a mistake, correct it. Even if, even the smallest of mistakes, we should correct. And, you know, I used to argue about that at The National on, on the desk, and people would say, "Oh, you know, it's a pretty small thing. We don't need to worry about that." I said, "Every time you correct something, you get a new viewer because they go if they're going to go to the trouble of correcting that, that tells me I can trust them." So it's one way, one way of getting at it.

Tony Parsons

Does it get your dander up when you hear Donald Trump say "fake news"?

Peter Mansbridge

Oh, yeah. Yeah. Now he's, you know, he gets credited with a lot of things that he shouldn't get credited for because the fake news argument has been around for decades, if not at least a century. Listen, there are two things which he, I mean, the guy's a liar. I mean, that's just a proven fact. We know that he's a con man. He's a bit of a con artist and a fraudster. He's been convicted of a variety of crimes, and yet he hasn't changed his ways. He's still, he still gets up there. He'll give a speech, a rambling speech that'll be full of misinformation or disinformation. And to get a handle on these, you got to understand the difference. Misinformation is basically a mistake, and people make mistakes, but you correct them. That's misinformation where you just get stuff wrong. Disinformation is a much more deliberate thing. It's when, you know, a special interest, it could be Trump, it could be a business, it could be any number of different things where they deliberately misinform you. That's disinformation. They're trying to get an end result by giving you bad information. That has to be challenged. And that's, you know, that's what we're here for, right? That's what the media, if media gets constantly criticized about Trump, how they cover Trump, that they just let him go. And he says all this stuff and they don't correct it. To a degree, that was certainly true in 2016 when he first came on the scene, they just let him go. Now they try to challenge him on this stuff. and he just, he bats it back and he slags the reporters or the journalists or ask them the questions. But they gotta keep at it. It's really difficult, and he's not alone. You know, I mean, we have fun going after Trump for lots of good reasons, but he's proven that a certain way of dealing with the media can be successful, not always, but sometimes. And so other politicians who've come along, you know, see, okay, this is a pathway I might be able to follow. And the more you get of that, the more trouble we're all in. And it's, you know, when, when, when we started, I mean, people get sick of old guys like us saying, "Oh, Oh, so different one. We were there." Yeah, right. Well, back in the day, you know, we had back in the day. I mean, it was different, but we still had con artists in politics. So they were around then as well. But it's a it's to a different level now. And journalists shouldn't be shy about standing up for the truth. And there are ways to do that without looking like you're trying to be a showman.

Tony Parsons

One of the most headline-stealing stories of the year happened not long ago with the release by Russia of prisoners in a prisoner swap that involved other countries as well. And one of the released prisoners worked for, I think, The Washington Post, but I'm not or anyway, he's an American journalist, and his name was Evan Gurskovich, and he was there for a long, long time as with some of the others. Does that tell you something about the risks now of being a journalist of that stature?

Peter Mansbridge

Sure, I think he was Wall Street Journal, but it doesn't matter, your point is correct. I mean, he was a significant journalist covering the Russian story from Moscow. He didn't, he didn't do anything wrong. It's usually the case in some of these grabs by the Russians. They're using them as bait to try and pull off a deal to get one of their own people released from an American jail, or in this case, a German jail. In terms of the safety of journalists, I mean, this has been a terrible year, mainly based on the Middle East situation. We've lost so many in the last year since October 7th, dozens of journalists have been killed in Gaza. But it continues a pattern where we've seen the risk for journalists in different places, whether it's being killed in action of some kind, where they've been trying to cover the story or they've been kidnapped. I mean, you know, Melissa Fung, who was a BC, you know, got a lot of her beginnings in journalism in BC, worked for the CBC, was in Afghanistan, was kidnapped and held in a hole in the ground for 30 days or a little longer than that. That was a terrible, awful situation, the things that happened to her. And I'll tell you, credit where it's due all you know all our her call media colleagues from all networks and use agencies banded together and understood the situation. But you know who was really responsible, I give him credit. It was Stephen Harper. He was Prime Minister at the time, and he was so totally offended by what had happened to Melissa, and that he pulled out all the stops to try and use diplomatic ways and others to bring that to a conclusion and free Melissa. But that was another example of what journalists have faced over these last 20 years especially. There's always been a danger for journalists covering various kinds of stories from whether they're wars or covering, you know, organized crime. That's why responsible news organizations now spend a great deal of their resources on ensuring the safety of their journalists who are on special assignments, whether it's in extra protection, whether it's in insurance, whether it's in monitoring very closely how they're dealing with the kind of situations they face out of the office. It's, you know, it's a tough world out there, and journalists—the men and women who work for the people in the sense they're trying to bring responsible information into our homes so we better understand the world we live in. Some of it's really difficult, and we owe them a lot. People ask me what's it like to be in a war zone because I've been in a few, but I've always been there as the anchor, so I'm in and out in a week, right? They're there for six months at a time. They're really dealing with the story. So I have enormous respect for them, and I get quite upset when I hear some politicians criticize the work they do when I realize what they're going through to do what they do.

Tony Parsons

Yeah, I say that about the wildfire situation. I think it takes a brave journalist to go do a job on the wildfire of a good reporter.

Peter Mansbridge

Sure. Yeah, but I'm wondering when something peaks your interest, when there's a big story, where do you go immediately? Do you go back to the CBC to watch what's going on?

Tony Parsons

I go all over the place, you know. I usually start like most people do by, you know, holding up my phone and going through, you know, one of the social media channels looking for sources that I trust. So it's not, you know, Joe Blow from wherever, it's, you know, The New York Times or The Globe and Mail or The Daily Telegraph in London. I mean, I surveyed the landscape and then if it's clear that whatever was rumored to be happening is happening, that's when I then go to usually an old news source of some kind, and it could be the CBC or CTV or MSNBC or CNN. Because by the time I get there, they've got cameras there. It's remarkable when you think of how, well, how we started, it might take days before you got a camera to the location here. It seems to be there in minutes. And it was usually a three or four man or person operation thing because you had a sound guy and then you'd go back to the station with film and hopefully the film was okay because you couldn't go out and shoot it again.

Peter Mansbridge

Yeah, it was different. Yeah, you try to explain. I do journalism school lecture and things like that. You try to explain film, like they look at you like you have four heads. But you'd have that hour or so to wait for the film to come back from the lab. And then you'd sit there with an editor and you'd actually cut the film, stick pieces together. It ain't like that anymore.

Tony Parsons

There's a lot of critical chatter going on these days about the CBC and how it is and what it's going to do. What's your observation?

Peter Mansbridge

Well, first of all, I don't mind critical chatter about the CBC. I've never minded that it's a public broadcaster. It costs the people of Canada more than a billion dollars a year to support it. And so they should chatter about it. And they should be continually talking about what they like and what they don't like. Because if you just leave it to the managers, that's not good enough. I'll try to be polite here. You need that feedback. I mean, we're supposedly serving the public, and the public should have a say. And if, first of all, if what you're seeing on there is not Canadian or have some Canadian aspect to it, then it's failing in its job. I mean, Canadians pay more than a billion dollars a year because it's the Canadian public broadcaster. It's not the American public broadcaster, not the European one. We're trying to give you a reflection of your country. That's what the CBC is supposed to be doing. Now, in today's world of television, especially, I mean, I think radio, nobody really complains about CBC radio that much. Anyway, they certainly like to complain about CBC television. And in today's world of television, it's a challenge on the landscape to make a successful operation. And so to do that, you need the support of people and you need the ideas from people. And where I think management has gone, especially in the recent years of the CBC, and it's easier for me obviously to talk now seeing as I'm not there, but is that they're not listening. As somebody said, the transmitter on the head of the top people of the CBC is always on transmit, it's not on receive. They're telling us what to think, where in fact, they should be listening. People are pretty sophisticated out there in terms of what they're watching these days, and there can be and there should be, and it's important that there is a market for good Canadian programming. Clearly, if they're not watching it now, they don't think it's good, so that's got to be something they keep in mind. Plus, with reducing budgets, and there's probably going to be more if the polls are right. You're going to have to make some tough decisions about where you want to spend money if the CBC survives. You can't do everything for everyone. So they're going to have to make some tough calls. Can it survive? I think the question is, should it survive? And I think I still maintain it should. I think it's really important that there's a Canadian public broadcaster that's devoted to that. When you flip through all the channels on your whatever kind of TV setup you have, there should be somewhere that you can instinctively know that's Canadian, that's the CBC, that's my CBC. If you're not able to do that, if it just looks like every other channel, then to hell with it. You know, spend the billion dollars on better healthcare, better education. What have you? You should be able to see that. You should be able to see that difference, know it right away.

Tony Parsons

One of the things that takes your time these days is a podcast much like this one. What do you think of this whole podcast phenomenon?

Peter Mansbridge

Yeah, I think it's, you know, obviously, I make a bit of a living with it now. So I'm going to say, yes, great, but it is great because it's the ability to bring all kinds of new ideas and thoughts to people's mind. The podcast audiences are really interesting people. Yeah, I got a lot of mail on, I have, I don't know, I get about 100,000 downloads a week on my podcast, which in podcast terms is quite a bit for Canadian podcasts. But I also get a lot of mail, people write to it. And I remember the kind of mail I used to get, whether it was emails, a real and back in the day, and half of those were like pretty kooky little weird some of those letters that would come in. Not so with the podcast audience.

Tony Parsons

Weird in what way?

Peter Mansbridge

Oh, well, you never knew what was coming, some of their ideas were crazy, and some of the things they included in their envelopes were a little bizarre. But anyway, today's mail is much different. It's thoughtful. It's smart. It's offering opinions and ideas. Not always ones I agree with, but they're thinking, which is what you're hoping to achieve when you do a podcast. And no matter what your subject is, I mean, I do five shows a week. One of them is sort of the best of from the past few years. But Mondays, I do international affairs. Tuesday is kind of like a feature interview, could be an author, could be a politician, could be whomever. Thursdays is, we call it your turn, which is basically some of this mail. When I started seeing the quality of the mail, I thought, "I got to share this, it's great stuff." And then Fridays is a political panel with Chantelle Bear, who I've worked with for 30 years, and Bruce Anderson, who's an analyst and pollster in Ottawa. And it's extremely popular. That's probably the most popular one of all. I think it's the number one political podcast in Canada, Canadian political podcast. And I, you know, I enjoy every day, I get up at six in the morning, five, five or six in the morning, and I do the shows, kind of between seven and eight, and then boom, off it goes. I send it off to Sirius, and they look after it from there, and then the podcast drops, the podcast version of it, drops at 12 noon Eastern time. And that's it, on to the next day. But there are thousands, as you know, thousands and thousands of podcasts, and so many of them are really good, really good, and they give you the time. They don't try to cram their thoughts and ideas and opinions in a couple of minutes. They talk for half an hour, 45 minutes, an hour. And you get a full, kind of a full version. If you're not interested, just switch it off, go to another one. But I think it's, you know, it's great. It's, you know, it's the furthering of democracy in many ways of getting your ideas out there and letting people listen to what you have to say. And it's fun. For me, it's been a bit of a, you know, all that time at the national, I wasn't allowed to have an opinion. Sometimes that was a break. Hey, Tony, you didn't have to. You didn't have to. I was a feeling about a particular thing. But now I have the option. If I want to say what I think about something, I just say it and don't feel like I'm breaking any kind of journalistic integrity rules. I just, this is my podcast.

Tony Parsons

I get this feeling that when I say I'm going to do a podcast, the person who I'm talking to says, "Well, there's an everybody."

Peter Mansbridge

There is a little of that, but you're the only one who's called Tony Parsons. And that, that makes a difference.

Tony Parsons

Peter, again, it's been a pleasure. Thanks so much for sharing your thoughts with us, and we hope we'll see you again soon.

Peter Mansbridge

That'd be nice. Take care.

The Tony Parsons Show is recorded and produced by Mike Peterson at 85 Audio in Kelowna, British Columbia. We'd like to send a massive thank you to our guest, Peter Mansbridge, for joining us on the show today. For more on Peter and for links to his podcast, The Bridge, visit his website, ThePeterMansbridge.com.

Have a question for Tony? You can send him an email at info@thetonyparsonsshow.com. For everything related to the podcast and more, visit us at thetonyparsonsshow.com. If you're enjoying what you're hearing, please consider leaving us a five-star rating or review on your streaming platform of choice.

We'll be back next week with another episode.

Read More

Tony Parsons

Hello, I'm Tony Parsons, and welcome to The Tony Parsons Show. As a news broadcaster and journalist for the past 50 years, I've reported on the major news events that have shaped our nation. I've interviewed prime ministers, premiers, thought leaders, and other people of distinction from around the world. My goal with this interview series is to help you, my audience, discover the person behind the credentials, while at the same time I'll invite them to share their professional insights, experiences, and aspirations.

I'm honored to welcome my colleague and fellow news broadcaster, Peter Mansbridge, to my show. As many of you are aware, Peter is best known for his five decades of work at the CBC, where he was chief correspondent of CBC News, and the anchor of The National for 30 years. He's won dozens of awards for outstanding journalism, has 13 honorary doctorates from universities in Canada and the United States, and received Canada's highest civilian honor, the Order of Canada in 2008. Now the host of the successful podcast, The Bridge.

Tony Parsons

Peter, I'd like to thank you for joining us today. It's great to have you with us.

Peter Mansbridge

It's great to be with you, Tony. I'm honored to be talking with you. I mean, it was very kind of you, all the nice things you say about me and my career. They could equally be said about you and yours. So it's an honor for me to be talking with you. Thank you very much. You know, I said "retired," but it seems to me that you're busier than you've ever been. I was thinking back to the first time you and I met, and that, if you recall, was at the University Golf Club. You were on the final green, I believe, and you were a judge, or were you running a contest for the putting?

Tony Parsons

Those were the old days of the Peter Russovsky Literacy Tournament. That's what it was. You and I supported Peter in his goals there, and they quickly learned that I wasn't much of a golfer, so they put me like on a putting grain, and I just pot against various people and collect a little more money out of them that way. But it was, that's a great golf course, a university golf course there, and it's a great area and met a lot of people there. I did that tournament, I guess, at least a half a dozen times. It was a great one, but always fun.

Peter Mansbridge

It was fun, it was a good time. I want to go back to the very beginning, and to the UK, where you were born, right?

Tony Parsons

Mm-hmm, I was. I was born in London in 1948.

Peter Mansbridge

We had kind of a similar background. Your dad was in the RAF. My dad was in the RAF. He was in bomber command, so he was based up at Lincoln with his Lancaster squad. And you know, had a distinguished career and war record as did your father. And that was the start, but I was only in England for a couple of years, because after the war, my parents, my dad was in the Foreign Service by then, and we went off to Kuala Lumpur in what was then Malaya to help it establish the independence and become Malaysia, as it did in the 1950s. And then we came to Canada, so I was when we came to Canada was about six, six years old, and we went to Otto. I was nine when we came here in 1948, and we went to a little town in Ontario called Feversham, about three, four hundred people after living in London for most of my young life and my poor mother. You can, you imagine, she cried for twelve days. It was just for her it was such a cult for shock. But my dad was, as you say, in the RAF, flight lieutenant, served in Iraq, and never got over the idea of wearing a uniform. He always loved to wear a uniform.

Tony Parsons

Let me take you back again, just a little bit. You were working in Winnipeg in an unusual job for now a broadcast journalist. You were discovered in Winnipeg?

Peter Mansbridge

Actually, I started working for an airline in Winnipeg, and they quickly moved me around. As this young kid, I was 19, 20 years old. Winnipeg was trained in Winnipeg. Then I worked in Brandon and Prince Albert. These were all for a couple of months at a time. Then they called me up and they said, "Hey, the guy in Churchill, the agent for our airline, which is called Transair, The guy in Churchill, Manitoba up on Hudson Bay is taking a holiday. So you got to go up there and fill in for him for two weeks. Nobody wanted to go to Churchill at that time, right? So up I went, and sure enough, a week after I'd been there, they called me up and said, "Hey, the guy quit. It's now your job. You're the new guy in Churchill." So that's what I was doing. And I was doing from loading freight to baggage, to selling tickets, to answering the phones, you name it, I did it all. Until one day they asked me to announce the flight over the PA system in the little terminal building. And it was a little, we're talking, this wasn't Vancouver International, this was Churchill, Manitoba, it was kind of one room. And so I got on there and I did, "Transair, Flight 106 for Thompson, The Pas, and Winnipeg now ready for boarding at gate one." There only was one gate, but it sounded really good. It sounded like the big boys did. And sure enough, there's somebody in the building, in the waiting room there, came up to me and said, "You've got a voice for radio. And I should know because I'm the manager of the CBC northern service station here in Churchill." And he said, "I can't get anybody to work the late night shift. And would you be interested?" And I said, "Well, I don't know anything about radio." And he said, "No, that wasn't the question. The question was, would you be interested?" So I said, "Sure." And so after a one-day course on how to run all the knobs on the control board, you know, those things from your days, you're in Stratford, Ontario, doing a country show or whatever it was you were doing on those days. Yeah, announce up, they used to call it. Yeah. So that's how I started. I started in Churchill, and it was the beginning of a 50-year career with the CBC.

Tony Parsons

Did you ever think you'd go on to replace Walt and Nash?

Peter Mansbridge

No, but you know, I thought about it. Even when I was in Churchill, because I, like you, I started with a music show. I was terrible at trying to understand music and stuff. And so I started a newscast. They didn't have one in Churchill, so I started one because I'd grown up in a family where we always kind of sat around the dinner table at night and talked about current events. And so I started a little, a little newscast. It was only like two or three minutes long when I'd started, and it eventually became half an hour of daily news in Churchill, which is quite something for a town of a thousand people. Um, but they had polar bears, which was always good for half the show every night. And so, you know, that's, that's how things started. And you kind of eventually make a name for yourself. And I was a reporter for 20 years before I started anchoring and then traveling all, all over the place in different locations.

Tony Parsons

How do you feel now about being retired?

Peter Mansbridge

It's interesting. I retired. I had told all my friends and I had told the CBC who wanted me to kept asking me to stay another year while they sorted things out, you know. I said, "I'm not, I am not going to do the national with a seven in front of my age. So take it from now that I'll be gone at 69." And I held true to that. And in 2015, I eventually gave them the clear signal, and by 2017, I was out. But I agreed to do some documentaries for the CBC for about a five-year period. And that was fun and a real experience for me. Having always been confronted with two-minute items and suddenly I was being given an hour to do a story, which was fantastic. But after that, I, you know, I wrote a, I've written four books since I retired. I do a, you know, a podcast like you, which is a lot of fun. I do it four days a week. It's on SiriusXM, the satellite radio service. And, you know, I give speeches. It sounds like I'm busier than I was, but like you, you do it in retirement, you do stuff at your own pace. I decide what I'm gonna do. Nobody's telling me what I have to do. I do things as I enjoy doing them and at my own pace. And I make sure I take the summers off, and I've just been doing that and it was great.

Tony Parsons

Looking back, what for you were some of the highlights of your career?

Peter Mansbridge

You know, I was so lucky because I got to work with so many great people, whether they were the people we see on the air, the correspondents, the reporters, or whether the people behind the scenes, the producers and the writers and the editors. And I think when people say, "Do you miss it?" I always say that's what I miss. I miss that camaraderie, that coming together to put a good product on the air and the feeling that you'd have at the end of the day and the discussions and the arguments that you'd have during the day about what needed to be on the program. So I miss that. I miss that a lot. And as I often tell young journalists who come to me and say, you know, "I'm not quite happy with where I am and what I'm doing." And I say, "Well, when you're in meetings for your program, what are those meetings like? Are they, you know, is there debate around what you're doing and covering?" And then they might say, "Oh, really?" I said, "Well, that's what you need. You need to be in a place in a newsroom where there is constant discussion and debate about the stories that you're covering." Now, you may have strong feelings they may end up not being accepted, but make the case. You know, try to convince others of what you're feeling or listen to the arguments of others, and maybe you'll be convinced by theirs, but you need that kind of discussion in a place. And I used to love those days. I mean, not every day was the exciting news day that we see in the movies. Some are kind of boring, and you're having a hard time trying to figure out what you're going to fill the program with.

Tony Parsons

True enough.

Peter Mansbridge

But a lot of days, you know, it was exciting, and it was, you know, it was worthy of the debate and the discussion. So I miss that. I miss, I miss the travel. I mean, I, you know, as first a reporter, and then as an anchor, when I accepted the anchor position and they asked me if I do that, I said, "Only if I can still travel occasionally, I want to get to the stories, especially whether it's, you know, where the national, it can't just be in downtown Toronto. You know, we got to be around." So, and one of my favorite places to go, and still is these days, was British Columbia. But I, you know, I did the national from every province, from all three territories, at least once, but usually half a dozen or a dozen times in some places. So that was important, but also traveling the world. And as the technology became easier and easier. As you said, Tony, you know, when we started, you had to, you know, sometimes to many half a dozen people with you to go on the road. They didn't have to be that way. It certainly doesn't have to be that way anymore for you to see about one-man band reporters where they do everything. They shoot it, they edit it, and they write it, and they do the whole bit. So it's a lot easier to take the show on the road as well. I took the show to Afghanistan a couple of times, to Iraq, to China, to all over Europe, the United States, South America, because it was not limiting by expense. It's only limiting by story. If you get to the story, you can tell the story, and you can tell it better when you're there than when you're in a studio in Toronto or Vancouver, wherever it happens to be. So I wanted to do that. Well, obviously, you couldn't do that all the time. But I did as much as I could in those days. I love, I love the thought of going to the airport, getting on a plane, and going off on some new adventure. So do I miss all that? Oh, yeah, absolutely. For sure, but you know, I was getting on, and it was time for younger blood, and I believe that then, and I believe it now, in whatever the job may be. I think there's definitely a need for experience and understanding based on what you've done in your career, but there's also a need for bringing new attitudes, new ideas into the system as well. So that's kind of where I land on that.

Tony Parsons

Things have changed now in the industry. What changes do you note that maybe social media has had a lot to do with?

Peter Mansbridge

Oh, yeah, it's pretty much everything to do with it. I mean, it started to change, and you remember this, it started to change in the 90s with the explosion of channels and competition and the 500 channel universe, and then the internet came and all these other options for news gathering started. And then when social media entered the picture, whether it was Facebook or Twitter or you name it, the challenge became deeper and more difficult because people were unsure of the nature of this new tool for social media, but they were more distrustful of its accuracy. And it's changed the face of the news business. Trust in news has slid. And there's no question about that, no matter who you watch, who you listen to, who you read. The client is questioning now because of disinformation and misinformation. What's accurate. And as you know, Tony, as well as anybody in the news business, truth is what matters. In fact, it's really all that matters is truth. And when you doubt that you're getting the truth, then you got a problem. And that's what all news organizations are trying to address now. And they thought it was going to be easy, it's not easy. And when you're at a point where people don't trust you, there's a serious question about the future for the news business. I mean, I'm sure we're gonna get through this, but it's tough right now. And people have a right to be concerned about the quality of the information they're getting.

Tony Parsons

Who would you have a rescue plan of any kind in your mind?

Peter Mansbridge

Well, I mean, it starts with making so many organizations more viable, more economically viable. You know, every day we read about another news organization or a broadcaster that's in trouble, is laying off people or shutting down. So that's one area of concern. Obviously, if you don't have the ability to be on the air or to print a newspaper, that's one part of the problem. But the other part is this trust thing. I really feel that we have to be more transparent. I keep talking about "we" Like it's like you and I are still in the business directly, but we're clients now so we're part of the picture, and we want to see a solution, and one solution on trust is to be more transparent about how we do our job. Like how do we decide what stories are worth telling? How do we decide what order they should be in? How do we decide how much time we should give to particular items? And then there's the more delicate stuff of, you know, when you start giving anonymity to certain sources to be able to break a story. How do you make that decision? Who gets anonymity? Who doesn't? How strongly do we look at their motives for wanting anonymity? Those are all issues that people worry about. When I talk to viewers or listeners or readers, those are the kind of questions they raise because they think we're biased or we're dealing in fake news and all that. So you have to be able to convince them that we're not, and to convince them we're not, you've got to show them how you do it, how you make the sausage. It's not always, you know, for them to, you can't do this every day, obviously, in a newscast, but every once in a while, you need to do it. You also need to admit when you're wrong. You know, you make a mistake, correct it. Even if, even the smallest of mistakes, we should correct. And, you know, I used to argue about that at The National on, on the desk, and people would say, "Oh, you know, it's a pretty small thing. We don't need to worry about that." I said, "Every time you correct something, you get a new viewer because they go if they're going to go to the trouble of correcting that, that tells me I can trust them." So it's one way, one way of getting at it.

Tony Parsons

Does it get your dander up when you hear Donald Trump say "fake news"?

Peter Mansbridge

Oh, yeah. Yeah. Now he's, you know, he gets credited with a lot of things that he shouldn't get credited for because the fake news argument has been around for decades, if not at least a century. Listen, there are two things which he, I mean, the guy's a liar. I mean, that's just a proven fact. We know that he's a con man. He's a bit of a con artist and a fraudster. He's been convicted of a variety of crimes, and yet he hasn't changed his ways. He's still, he still gets up there. He'll give a speech, a rambling speech that'll be full of misinformation or disinformation. And to get a handle on these, you got to understand the difference. Misinformation is basically a mistake, and people make mistakes, but you correct them. That's misinformation where you just get stuff wrong. Disinformation is a much more deliberate thing. It's when, you know, a special interest, it could be Trump, it could be a business, it could be any number of different things where they deliberately misinform you. That's disinformation. They're trying to get an end result by giving you bad information. That has to be challenged. And that's, you know, that's what we're here for, right? That's what the media, if media gets constantly criticized about Trump, how they cover Trump, that they just let him go. And he says all this stuff and they don't correct it. To a degree, that was certainly true in 2016 when he first came on the scene, they just let him go. Now they try to challenge him on this stuff. and he just, he bats it back and he slags the reporters or the journalists or ask them the questions. But they gotta keep at it. It's really difficult, and he's not alone. You know, I mean, we have fun going after Trump for lots of good reasons, but he's proven that a certain way of dealing with the media can be successful, not always, but sometimes. And so other politicians who've come along, you know, see, okay, this is a pathway I might be able to follow. And the more you get of that, the more trouble we're all in. And it's, you know, when, when, when we started, I mean, people get sick of old guys like us saying, "Oh, Oh, so different one. We were there." Yeah, right. Well, back in the day, you know, we had back in the day. I mean, it was different, but we still had con artists in politics. So they were around then as well. But it's a it's to a different level now. And journalists shouldn't be shy about standing up for the truth. And there are ways to do that without looking like you're trying to be a showman.

Tony Parsons

One of the most headline-stealing stories of the year happened not long ago with the release by Russia of prisoners in a prisoner swap that involved other countries as well. And one of the released prisoners worked for, I think, The Washington Post, but I'm not or anyway, he's an American journalist, and his name was Evan Gurskovich, and he was there for a long, long time as with some of the others. Does that tell you something about the risks now of being a journalist of that stature?

Peter Mansbridge

Sure, I think he was Wall Street Journal, but it doesn't matter, your point is correct. I mean, he was a significant journalist covering the Russian story from Moscow. He didn't, he didn't do anything wrong. It's usually the case in some of these grabs by the Russians. They're using them as bait to try and pull off a deal to get one of their own people released from an American jail, or in this case, a German jail. In terms of the safety of journalists, I mean, this has been a terrible year, mainly based on the Middle East situation. We've lost so many in the last year since October 7th, dozens of journalists have been killed in Gaza. But it continues a pattern where we've seen the risk for journalists in different places, whether it's being killed in action of some kind, where they've been trying to cover the story or they've been kidnapped. I mean, you know, Melissa Fung, who was a BC, you know, got a lot of her beginnings in journalism in BC, worked for the CBC, was in Afghanistan, was kidnapped and held in a hole in the ground for 30 days or a little longer than that. That was a terrible, awful situation, the things that happened to her. And I'll tell you, credit where it's due all you know all our her call media colleagues from all networks and use agencies banded together and understood the situation. But you know who was really responsible, I give him credit. It was Stephen Harper. He was Prime Minister at the time, and he was so totally offended by what had happened to Melissa, and that he pulled out all the stops to try and use diplomatic ways and others to bring that to a conclusion and free Melissa. But that was another example of what journalists have faced over these last 20 years especially. There's always been a danger for journalists covering various kinds of stories from whether they're wars or covering, you know, organized crime. That's why responsible news organizations now spend a great deal of their resources on ensuring the safety of their journalists who are on special assignments, whether it's in extra protection, whether it's in insurance, whether it's in monitoring very closely how they're dealing with the kind of situations they face out of the office. It's, you know, it's a tough world out there, and journalists—the men and women who work for the people in the sense they're trying to bring responsible information into our homes so we better understand the world we live in. Some of it's really difficult, and we owe them a lot. People ask me what's it like to be in a war zone because I've been in a few, but I've always been there as the anchor, so I'm in and out in a week, right? They're there for six months at a time. They're really dealing with the story. So I have enormous respect for them, and I get quite upset when I hear some politicians criticize the work they do when I realize what they're going through to do what they do.

Tony Parsons

Yeah, I say that about the wildfire situation. I think it takes a brave journalist to go do a job on the wildfire of a good reporter.

Peter Mansbridge

Sure. Yeah, but I'm wondering when something peaks your interest, when there's a big story, where do you go immediately? Do you go back to the CBC to watch what's going on?

Tony Parsons

I go all over the place, you know. I usually start like most people do by, you know, holding up my phone and going through, you know, one of the social media channels looking for sources that I trust. So it's not, you know, Joe Blow from wherever, it's, you know, The New York Times or The Globe and Mail or The Daily Telegraph in London. I mean, I surveyed the landscape and then if it's clear that whatever was rumored to be happening is happening, that's when I then go to usually an old news source of some kind, and it could be the CBC or CTV or MSNBC or CNN. Because by the time I get there, they've got cameras there. It's remarkable when you think of how, well, how we started, it might take days before you got a camera to the location here. It seems to be there in minutes. And it was usually a three or four man or person operation thing because you had a sound guy and then you'd go back to the station with film and hopefully the film was okay because you couldn't go out and shoot it again.

Peter Mansbridge

Yeah, it was different. Yeah, you try to explain. I do journalism school lecture and things like that. You try to explain film, like they look at you like you have four heads. But you'd have that hour or so to wait for the film to come back from the lab. And then you'd sit there with an editor and you'd actually cut the film, stick pieces together. It ain't like that anymore.

Tony Parsons

There's a lot of critical chatter going on these days about the CBC and how it is and what it's going to do. What's your observation?

Peter Mansbridge

Well, first of all, I don't mind critical chatter about the CBC. I've never minded that it's a public broadcaster. It costs the people of Canada more than a billion dollars a year to support it. And so they should chatter about it. And they should be continually talking about what they like and what they don't like. Because if you just leave it to the managers, that's not good enough. I'll try to be polite here. You need that feedback. I mean, we're supposedly serving the public, and the public should have a say. And if, first of all, if what you're seeing on there is not Canadian or have some Canadian aspect to it, then it's failing in its job. I mean, Canadians pay more than a billion dollars a year because it's the Canadian public broadcaster. It's not the American public broadcaster, not the European one. We're trying to give you a reflection of your country. That's what the CBC is supposed to be doing. Now, in today's world of television, especially, I mean, I think radio, nobody really complains about CBC radio that much. Anyway, they certainly like to complain about CBC television. And in today's world of television, it's a challenge on the landscape to make a successful operation. And so to do that, you need the support of people and you need the ideas from people. And where I think management has gone, especially in the recent years of the CBC, and it's easier for me obviously to talk now seeing as I'm not there, but is that they're not listening. As somebody said, the transmitter on the head of the top people of the CBC is always on transmit, it's not on receive. They're telling us what to think, where in fact, they should be listening. People are pretty sophisticated out there in terms of what they're watching these days, and there can be and there should be, and it's important that there is a market for good Canadian programming. Clearly, if they're not watching it now, they don't think it's good, so that's got to be something they keep in mind. Plus, with reducing budgets, and there's probably going to be more if the polls are right. You're going to have to make some tough decisions about where you want to spend money if the CBC survives. You can't do everything for everyone. So they're going to have to make some tough calls. Can it survive? I think the question is, should it survive? And I think I still maintain it should. I think it's really important that there's a Canadian public broadcaster that's devoted to that. When you flip through all the channels on your whatever kind of TV setup you have, there should be somewhere that you can instinctively know that's Canadian, that's the CBC, that's my CBC. If you're not able to do that, if it just looks like every other channel, then to hell with it. You know, spend the billion dollars on better healthcare, better education. What have you? You should be able to see that. You should be able to see that difference, know it right away.

Tony Parsons

One of the things that takes your time these days is a podcast much like this one. What do you think of this whole podcast phenomenon?

Peter Mansbridge

Yeah, I think it's, you know, obviously, I make a bit of a living with it now. So I'm going to say, yes, great, but it is great because it's the ability to bring all kinds of new ideas and thoughts to people's mind. The podcast audiences are really interesting people. Yeah, I got a lot of mail on, I have, I don't know, I get about 100,000 downloads a week on my podcast, which in podcast terms is quite a bit for Canadian podcasts. But I also get a lot of mail, people write to it. And I remember the kind of mail I used to get, whether it was emails, a real and back in the day, and half of those were like pretty kooky little weird some of those letters that would come in. Not so with the podcast audience.

Tony Parsons

Weird in what way?

Peter Mansbridge

Oh, well, you never knew what was coming, some of their ideas were crazy, and some of the things they included in their envelopes were a little bizarre. But anyway, today's mail is much different. It's thoughtful. It's smart. It's offering opinions and ideas. Not always ones I agree with, but they're thinking, which is what you're hoping to achieve when you do a podcast. And no matter what your subject is, I mean, I do five shows a week. One of them is sort of the best of from the past few years. But Mondays, I do international affairs. Tuesday is kind of like a feature interview, could be an author, could be a politician, could be whomever. Thursdays is, we call it your turn, which is basically some of this mail. When I started seeing the quality of the mail, I thought, "I got to share this, it's great stuff." And then Fridays is a political panel with Chantelle Bear, who I've worked with for 30 years, and Bruce Anderson, who's an analyst and pollster in Ottawa. And it's extremely popular. That's probably the most popular one of all. I think it's the number one political podcast in Canada, Canadian political podcast. And I, you know, I enjoy every day, I get up at six in the morning, five, five or six in the morning, and I do the shows, kind of between seven and eight, and then boom, off it goes. I send it off to Sirius, and they look after it from there, and then the podcast drops, the podcast version of it, drops at 12 noon Eastern time. And that's it, on to the next day. But there are thousands, as you know, thousands and thousands of podcasts, and so many of them are really good, really good, and they give you the time. They don't try to cram their thoughts and ideas and opinions in a couple of minutes. They talk for half an hour, 45 minutes, an hour. And you get a full, kind of a full version. If you're not interested, just switch it off, go to another one. But I think it's, you know, it's great. It's, you know, it's the furthering of democracy in many ways of getting your ideas out there and letting people listen to what you have to say. And it's fun. For me, it's been a bit of a, you know, all that time at the national, I wasn't allowed to have an opinion. Sometimes that was a break. Hey, Tony, you didn't have to. You didn't have to. I was a feeling about a particular thing. But now I have the option. If I want to say what I think about something, I just say it and don't feel like I'm breaking any kind of journalistic integrity rules. I just, this is my podcast.

Tony Parsons

I get this feeling that when I say I'm going to do a podcast, the person who I'm talking to says, "Well, there's an everybody."

Peter Mansbridge

There is a little of that, but you're the only one who's called Tony Parsons. And that, that makes a difference.

Tony Parsons

Peter, again, it's been a pleasure. Thanks so much for sharing your thoughts with us, and we hope we'll see you again soon.

Peter Mansbridge

That'd be nice. Take care.

The Tony Parsons Show is recorded and produced by Mike Peterson at 85 Audio in Kelowna, British Columbia. We'd like to send a massive thank you to our guest, Peter Mansbridge, for joining us on the show today. For more on Peter and for links to his podcast, The Bridge, visit his website, ThePeterMansbridge.com.

Have a question for Tony? You can send him an email at info@thetonyparsonsshow.com. For everything related to the podcast and more, visit us at thetonyparsonsshow.com. If you're enjoying what you're hearing, please consider leaving us a five-star rating or review on your streaming platform of choice.

We'll be back next week with another episode.

Read More

Tony Parsons

Hello, I'm Tony Parsons, and welcome to The Tony Parsons Show. As a news broadcaster and journalist for the past 50 years, I've reported on the major news events that have shaped our nation. I've interviewed prime ministers, premiers, thought leaders, and other people of distinction from around the world. My goal with this interview series is to help you, my audience, discover the person behind the credentials, while at the same time I'll invite them to share their professional insights, experiences, and aspirations.

I'm honored to welcome my colleague and fellow news broadcaster, Peter Mansbridge, to my show. As many of you are aware, Peter is best known for his five decades of work at the CBC, where he was chief correspondent of CBC News, and the anchor of The National for 30 years. He's won dozens of awards for outstanding journalism, has 13 honorary doctorates from universities in Canada and the United States, and received Canada's highest civilian honor, the Order of Canada in 2008. Now the host of the successful podcast, The Bridge.

Tony Parsons

Peter, I'd like to thank you for joining us today. It's great to have you with us.

Peter Mansbridge

It's great to be with you, Tony. I'm honored to be talking with you. I mean, it was very kind of you, all the nice things you say about me and my career. They could equally be said about you and yours. So it's an honor for me to be talking with you. Thank you very much. You know, I said "retired," but it seems to me that you're busier than you've ever been. I was thinking back to the first time you and I met, and that, if you recall, was at the University Golf Club. You were on the final green, I believe, and you were a judge, or were you running a contest for the putting?

Tony Parsons

Those were the old days of the Peter Russovsky Literacy Tournament. That's what it was. You and I supported Peter in his goals there, and they quickly learned that I wasn't much of a golfer, so they put me like on a putting grain, and I just pot against various people and collect a little more money out of them that way. But it was, that's a great golf course, a university golf course there, and it's a great area and met a lot of people there. I did that tournament, I guess, at least a half a dozen times. It was a great one, but always fun.

Peter Mansbridge

It was fun, it was a good time. I want to go back to the very beginning, and to the UK, where you were born, right?

Tony Parsons

Mm-hmm, I was. I was born in London in 1948.

Peter Mansbridge

We had kind of a similar background. Your dad was in the RAF. My dad was in the RAF. He was in bomber command, so he was based up at Lincoln with his Lancaster squad. And you know, had a distinguished career and war record as did your father. And that was the start, but I was only in England for a couple of years, because after the war, my parents, my dad was in the Foreign Service by then, and we went off to Kuala Lumpur in what was then Malaya to help it establish the independence and become Malaysia, as it did in the 1950s. And then we came to Canada, so I was when we came to Canada was about six, six years old, and we went to Otto. I was nine when we came here in 1948, and we went to a little town in Ontario called Feversham, about three, four hundred people after living in London for most of my young life and my poor mother. You can, you imagine, she cried for twelve days. It was just for her it was such a cult for shock. But my dad was, as you say, in the RAF, flight lieutenant, served in Iraq, and never got over the idea of wearing a uniform. He always loved to wear a uniform.

Tony Parsons

Let me take you back again, just a little bit. You were working in Winnipeg in an unusual job for now a broadcast journalist. You were discovered in Winnipeg?

Peter Mansbridge

Actually, I started working for an airline in Winnipeg, and they quickly moved me around. As this young kid, I was 19, 20 years old. Winnipeg was trained in Winnipeg. Then I worked in Brandon and Prince Albert. These were all for a couple of months at a time. Then they called me up and they said, "Hey, the guy in Churchill, the agent for our airline, which is called Transair, The guy in Churchill, Manitoba up on Hudson Bay is taking a holiday. So you got to go up there and fill in for him for two weeks. Nobody wanted to go to Churchill at that time, right? So up I went, and sure enough, a week after I'd been there, they called me up and said, "Hey, the guy quit. It's now your job. You're the new guy in Churchill." So that's what I was doing. And I was doing from loading freight to baggage, to selling tickets, to answering the phones, you name it, I did it all. Until one day they asked me to announce the flight over the PA system in the little terminal building. And it was a little, we're talking, this wasn't Vancouver International, this was Churchill, Manitoba, it was kind of one room. And so I got on there and I did, "Transair, Flight 106 for Thompson, The Pas, and Winnipeg now ready for boarding at gate one." There only was one gate, but it sounded really good. It sounded like the big boys did. And sure enough, there's somebody in the building, in the waiting room there, came up to me and said, "You've got a voice for radio. And I should know because I'm the manager of the CBC northern service station here in Churchill." And he said, "I can't get anybody to work the late night shift. And would you be interested?" And I said, "Well, I don't know anything about radio." And he said, "No, that wasn't the question. The question was, would you be interested?" So I said, "Sure." And so after a one-day course on how to run all the knobs on the control board, you know, those things from your days, you're in Stratford, Ontario, doing a country show or whatever it was you were doing on those days. Yeah, announce up, they used to call it. Yeah. So that's how I started. I started in Churchill, and it was the beginning of a 50-year career with the CBC.

Tony Parsons

Did you ever think you'd go on to replace Walt and Nash?

Peter Mansbridge

No, but you know, I thought about it. Even when I was in Churchill, because I, like you, I started with a music show. I was terrible at trying to understand music and stuff. And so I started a newscast. They didn't have one in Churchill, so I started one because I'd grown up in a family where we always kind of sat around the dinner table at night and talked about current events. And so I started a little, a little newscast. It was only like two or three minutes long when I'd started, and it eventually became half an hour of daily news in Churchill, which is quite something for a town of a thousand people. Um, but they had polar bears, which was always good for half the show every night. And so, you know, that's, that's how things started. And you kind of eventually make a name for yourself. And I was a reporter for 20 years before I started anchoring and then traveling all, all over the place in different locations.

Tony Parsons

How do you feel now about being retired?

Peter Mansbridge

It's interesting. I retired. I had told all my friends and I had told the CBC who wanted me to kept asking me to stay another year while they sorted things out, you know. I said, "I'm not, I am not going to do the national with a seven in front of my age. So take it from now that I'll be gone at 69." And I held true to that. And in 2015, I eventually gave them the clear signal, and by 2017, I was out. But I agreed to do some documentaries for the CBC for about a five-year period. And that was fun and a real experience for me. Having always been confronted with two-minute items and suddenly I was being given an hour to do a story, which was fantastic. But after that, I, you know, I wrote a, I've written four books since I retired. I do a, you know, a podcast like you, which is a lot of fun. I do it four days a week. It's on SiriusXM, the satellite radio service. And, you know, I give speeches. It sounds like I'm busier than I was, but like you, you do it in retirement, you do stuff at your own pace. I decide what I'm gonna do. Nobody's telling me what I have to do. I do things as I enjoy doing them and at my own pace. And I make sure I take the summers off, and I've just been doing that and it was great.

Tony Parsons

Looking back, what for you were some of the highlights of your career?

Peter Mansbridge

You know, I was so lucky because I got to work with so many great people, whether they were the people we see on the air, the correspondents, the reporters, or whether the people behind the scenes, the producers and the writers and the editors. And I think when people say, "Do you miss it?" I always say that's what I miss. I miss that camaraderie, that coming together to put a good product on the air and the feeling that you'd have at the end of the day and the discussions and the arguments that you'd have during the day about what needed to be on the program. So I miss that. I miss that a lot. And as I often tell young journalists who come to me and say, you know, "I'm not quite happy with where I am and what I'm doing." And I say, "Well, when you're in meetings for your program, what are those meetings like? Are they, you know, is there debate around what you're doing and covering?" And then they might say, "Oh, really?" I said, "Well, that's what you need. You need to be in a place in a newsroom where there is constant discussion and debate about the stories that you're covering." Now, you may have strong feelings they may end up not being accepted, but make the case. You know, try to convince others of what you're feeling or listen to the arguments of others, and maybe you'll be convinced by theirs, but you need that kind of discussion in a place. And I used to love those days. I mean, not every day was the exciting news day that we see in the movies. Some are kind of boring, and you're having a hard time trying to figure out what you're going to fill the program with.

Tony Parsons

True enough.

Peter Mansbridge

But a lot of days, you know, it was exciting, and it was, you know, it was worthy of the debate and the discussion. So I miss that. I miss, I miss the travel. I mean, I, you know, as first a reporter, and then as an anchor, when I accepted the anchor position and they asked me if I do that, I said, "Only if I can still travel occasionally, I want to get to the stories, especially whether it's, you know, where the national, it can't just be in downtown Toronto. You know, we got to be around." So, and one of my favorite places to go, and still is these days, was British Columbia. But I, you know, I did the national from every province, from all three territories, at least once, but usually half a dozen or a dozen times in some places. So that was important, but also traveling the world. And as the technology became easier and easier. As you said, Tony, you know, when we started, you had to, you know, sometimes to many half a dozen people with you to go on the road. They didn't have to be that way. It certainly doesn't have to be that way anymore for you to see about one-man band reporters where they do everything. They shoot it, they edit it, and they write it, and they do the whole bit. So it's a lot easier to take the show on the road as well. I took the show to Afghanistan a couple of times, to Iraq, to China, to all over Europe, the United States, South America, because it was not limiting by expense. It's only limiting by story. If you get to the story, you can tell the story, and you can tell it better when you're there than when you're in a studio in Toronto or Vancouver, wherever it happens to be. So I wanted to do that. Well, obviously, you couldn't do that all the time. But I did as much as I could in those days. I love, I love the thought of going to the airport, getting on a plane, and going off on some new adventure. So do I miss all that? Oh, yeah, absolutely. For sure, but you know, I was getting on, and it was time for younger blood, and I believe that then, and I believe it now, in whatever the job may be. I think there's definitely a need for experience and understanding based on what you've done in your career, but there's also a need for bringing new attitudes, new ideas into the system as well. So that's kind of where I land on that.

Tony Parsons

Things have changed now in the industry. What changes do you note that maybe social media has had a lot to do with?

Peter Mansbridge

Oh, yeah, it's pretty much everything to do with it. I mean, it started to change, and you remember this, it started to change in the 90s with the explosion of channels and competition and the 500 channel universe, and then the internet came and all these other options for news gathering started. And then when social media entered the picture, whether it was Facebook or Twitter or you name it, the challenge became deeper and more difficult because people were unsure of the nature of this new tool for social media, but they were more distrustful of its accuracy. And it's changed the face of the news business. Trust in news has slid. And there's no question about that, no matter who you watch, who you listen to, who you read. The client is questioning now because of disinformation and misinformation. What's accurate. And as you know, Tony, as well as anybody in the news business, truth is what matters. In fact, it's really all that matters is truth. And when you doubt that you're getting the truth, then you got a problem. And that's what all news organizations are trying to address now. And they thought it was going to be easy, it's not easy. And when you're at a point where people don't trust you, there's a serious question about the future for the news business. I mean, I'm sure we're gonna get through this, but it's tough right now. And people have a right to be concerned about the quality of the information they're getting.

Tony Parsons

Who would you have a rescue plan of any kind in your mind?

Peter Mansbridge